|

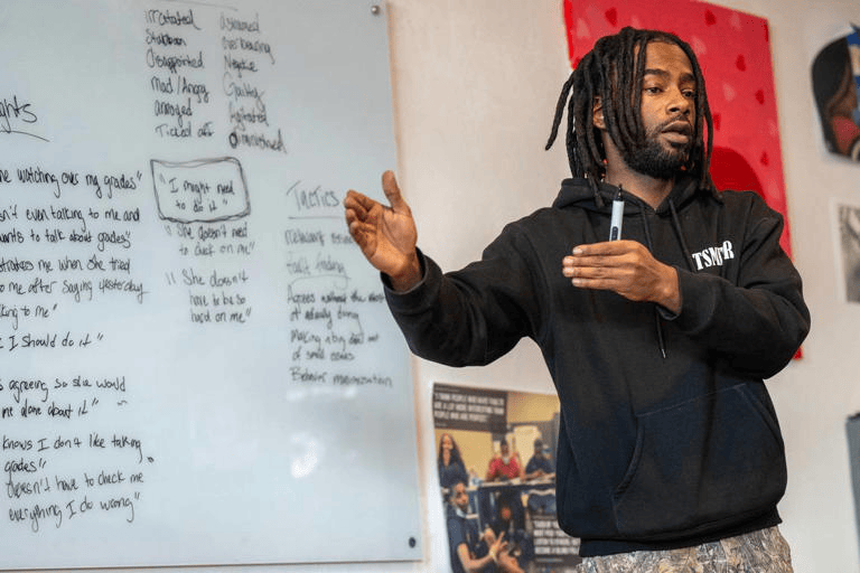

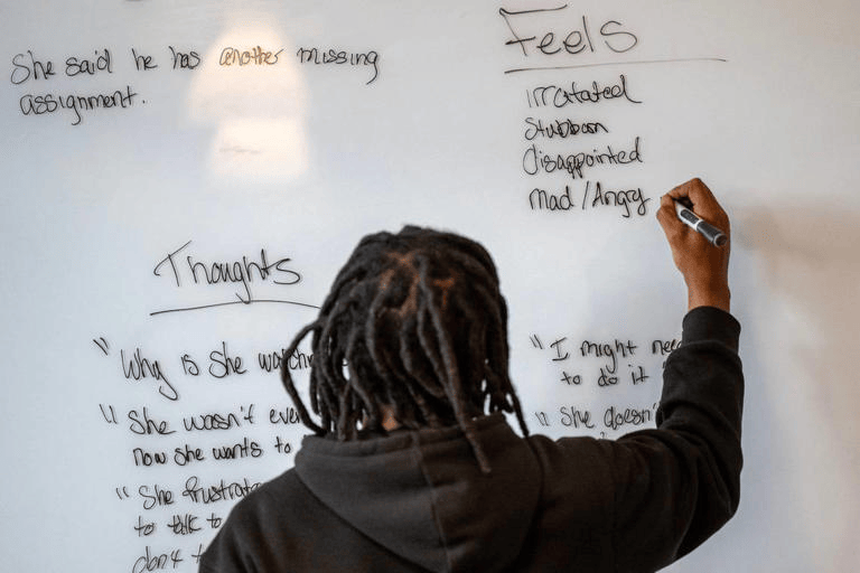

The Lyrik Institution, founded in 2019 has served over 1,000 inner city young people, ages 13 to 25.© Emily Curiel/[email protected]/Kansas City Star/TNS Story by J.M. Banks, The Kansas City Star Kyle Hollins grew up in an environment where the wrong comment or look could lead to a catastrophic chain of life altering events. He now spends his days in front of local youth working to quash the thought processes in them that could lead to the kind of violent actions that altered his life course in a negative way. Hollins is the founder of the Lyrik Institution, a nonprofit that has gained a reputation for connecting with those unreachable to most. As someone who has lived through the reality that the kids and young adults in his organization face every day, Hollins believes that many children are programmed for survival. Hollins himself faced homelessness, gang involvement and crime all before the age of 18. He knows firsthand that living that life too often leads young people into a prison cell or an early grave. Janese B. Williams, cultural coach, assists young people attending the Lyrik’s Institution with lesson plans, workshops and mentoring.© Emily Curiel/[email protected]/Kansas City Star/TNS He knows that young people, at risk of getting caught in this type of life, need to see that there are different paths to choose, different and more meaningful possibilities for survival. They need someone who they can relate to to teach them new ways of thinking about how to navigate their lives, despite whatever challenging social circumstances that, through no fault of their own, they may find themselves in. Ryan Harvey, cultural coach, writes on a white board the feelings students express while being in a lecture at Lyrik’s Institution.© Emily Curiel/[email protected]/Kansas City Star/TNS

Hollins, the recipient of Kansas City’s 2023 Pinnacle Prize for engagement, gives young Lyrik clients exactly that. The Lyrik Institution has seen a great deal of success in its few short years of existence. Founded in 2019, the organization has served over 1,000 inner city young people, ages 13 to 25. It’s a program that Hollins believes might have made a big difference in the early years of his own life. Without his father in the house, Hollins turned to the men in his community who had the things he wanted. He began to follow their lead to become what he thought a “real man” was. Hollins sank deep into street life and eventually found himself serving seven years in a federal prison on felony drug and weapons charges. He was locked up at Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary when his real education began. “I am completely self-taught,” says Hollins. “The bulk of my education didn’t come from your traditional school institution. It was lived experience.” Hollins used his time in prison to study. He embraced opportunities offered there such as cognitive behavior modification, a form of therapy that targets negative though patterns and breaking them. After completing an 18-month course, Hollins began developing a plan for how he could use his mistakes to reach the next generation. “I was shot in the chest at age 18,” says the 36-year-old Kansas City native. “I realized that I wasn’t as smart as I thought I was. I was making bad decision after bad decision.” He was eager to find uses for his newly honed skills. Hollins became a peer coach in prison and heard from fellow prisoners that they shared similar life experiences and about how the street life and their bad choices had lead to their incarceration. Hollins knew that nothing was going to change without aiding the next generation in unlearning the negative thinking that lead youth down a wayward path. The young people Hollins works with at Lyrik are adverse to sitting in a traditional classroom and being told by teachers and other educators who don’t come from where they come from, about what is wrong with the life choices they are making. He understands these young people because he’s has been there. The kids and young adults who listen to Hollins, see him as a living example of choices and consequences. “We can’t get out of this cycle until somebody exposes us to it and shows us who we really are,” he says. Becoming dedicated to getting out of prison and starting over came from a commitment he made to personal growth that Hollins attributes to his daughter, Lyrik, the namesake of his organization. “I remember getting a phone call from my daughter while I was locked up,” says Hollins. “She was crying and telling me how hard it was without me and I was like, wow, now I am not in her life when she needs me so I am adding to the cycle. I knew I had to get out and make a change.” When he got out of prison, Hollins wrote numerous letters to influential people and civic organizations asking how he might best serve the community. To his surprise, he got answers. Overjoyed to learn that people were not only interested, but excited, about the prospect that someone who himself had been involved in street life — fighting, drugs and crime — might be exactly the way to reach and turn around inner city youth who are traveling on the wrong path. “There is a level of trust involved with what we do,” says Hollins. “We are able to lock in with young adults that a lot of programs cannot get to.” Artez Thomas, 21, learned about the program from a past teacher who had kept in touch with him and saw his life on the decline. She challenged him to take a chance and attend sessions at Lyrik. “I went into it with an open mind, like, let me learn something new,” says Thomas. “Before this I was just living at a fast pace, hanging out with people, drinking, smoking and I had to get out of that.” Thomas, a father of five, wanted to get his life together so he could become a better dad to his children. Lacking the proper guidance as a child, he thinks himself lucky to have found a place where he can gain life skills that were not thoroughly drilled into him before now. Building a bond with Hollins, he was able to open up about the issues that have negatively impacted his life the most and develop a plan of action on how to move forward. “There have been some very important lessons like accountability,” says Thomas. “I do not hold myself accountable for doing the things I know I should and realizing how much the things I do affect the people around me. Just being able to say I am wrong is huge for me.” Hollins’ organization is set up to provide two-hour mentoring sessions and workshops every day during after-school hours. Participation is strictly voluntary, but he says that for most, after they attend one session they come back. “We shape the thought process once we build the relationship,” says Hollins. Michael Williams, a student at the Lyrik Institution joined the program this year. He was signed up by his mother who heard about the organization and wanted her son around positive influences. “We get to go into the not so pretty places of life,” says the 17 year old recent graduate of Frontier STEM High School. “This place helps with the teen transition where we are trying to find the disconnect because adolescence comes with a lot of problems.” Williams hopes to get a job at Ford Motor Company.He too is thankful that he had the opportunity to work with Hollins and from him learn skills like money management, emotional intelligence and problem solving. Mike says that he would encourage others to attend sessions at Lyrik. “I thought that I was comfortable with myself,” he says. Hollins knows many of the young people he has helped were just kids who never were asked simple questions about who they were and where they wanted to be. “It is about being authentic,” says Hollins. “Once they rock with you they are thankful for those life lessons and grateful to have someone who cares enough not to let them go down that path.” ©2024 The Kansas City Star. Visit kansascity.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

April 2024

Categories |

Lyrik's InstituteOur Mission

Our Mission is to reduce crime and violence by targeting destructive thinking errors and reworking them into productive behaviors. |

|

© Lyrik's Institution. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed